Dracula: From Sexual Predator to Romantic Hero

As the sun sinks beneath the horizon and night descends upon the world, humanity huddles around the collective light to fend off the threats within the darkness. In ancient times, this was often equated with the fear of predators, red in tooth and claw, but as humans abandoned their caves and huts for more cosmopolitan climes, the dangers began to take on a more familiar appearance. Senseless crimes such as murder would often be attributed to strange, supernatural beings -- after all, in the eyes of early man, no human could possibly do something so heinous to their kin. As such, tales of blood-sucking demons such as the draugr of Scandinavia, vrykolakas of Greece, and vetālas of India began to rise in prominence all over the world. Though the word “vampire” would not be coined for many centuries, all of these legends speak to a baser human fear of those who would prey upon their own kind. In the 19th Century, the Vampire suddenly took center stage after a series of groundbreaking novels, such as John Polidori’s The Vampyre, Sheridan LeFanu’s Carmilla, and finally and most famously, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Monumentally successful, Dracula’s gothic story and thinly veiled eroticism titillated its stodgy, Victorian reader-base, and would cement itself as one of the seminal works of fiction in the Western world. Contemporaneously, the advent of the motion picture began its own meteoric rise. As though destined for one another, the vampire and the film share a great many commonalities -- both present figures trapped in immortality, an illusion that can reveal great beauty, or horror -- it is perhaps no surprise that the vampire, and by extension, Dracula himself, has become one of the most popular subjects in film. Though consistently present in nearly every era of filmmaking, the bloodsucking Count has evolved greatly from his first adaptation to his more modern incarnations. What once was a monster that haunted our nightmares has now become a figure that pervades our fantasies, separating us into those who wish to become him, or even his victim.

Upon the novel’s original publication, the character of Count Dracula represented everything that a Victorian audience would find distasteful. Strange, lustful, and above all else, foreign, the Count’s unsettling visage is first described by one of the novel’s protagonists, Jonathan Harker: “His face was a strong – a very strong – aquiline, with high bridge of the thin nose and peculiarly arched nostrils; with lofty domed forehead, and hair growing scantily round the temples, but profusely elsewhere. ... The mouth, so far as I could see it under the heavy moustache, was fixed and rather cruel-looking, with peculiarly sharp white teeth” (Stoker 27).

To the contemporary reader, such a strange appearance would largely be attributed to the character’s undead nature -- but in the 19th century such descriptions played upon the ingrained prejudices and xenophobia of Victorian England. Far from the gentleman vampire of later depictions, the prospect of this loathsome figure leaving his ancestral home in far-off Transylvania in favor of the streets of London to prey upon gentle English women was as horrifying of a prospect as could be imagined. What’s worse, the depredations of the Count would mean not only death for his victims, but their corruption. Truly, the concept of being turned into a creature as base and unapologetic as he seemed a fate far worse than death. In spite of his hideous mien, Stoker’s primary inspiration behind Count Dracula reportedly came from the larger-than-life presence found within his longtime associate, stage-actor Henry Irving. Historian Louis Warren writes: “Scholars have long agreed that keys to the Dracula tale's origin and meaning lie in the manager's relationship with Irving in the 1880s. … There is virtual unanimity on the point that the figure of Dracula—which Stoker began to write notes for in 1890—was inspired by Henry Irving himself” (Warren). Having written Dracula as a framework for a possible stage-play, Stoker knew even then that the character required a magnetic majesty, an ability to intrigue as well as revile. And though Stoker’s play, starring Irving, would never see proverbial daylight, this approach to casting the titular Count would be echoed through the ages and his various adaptations.

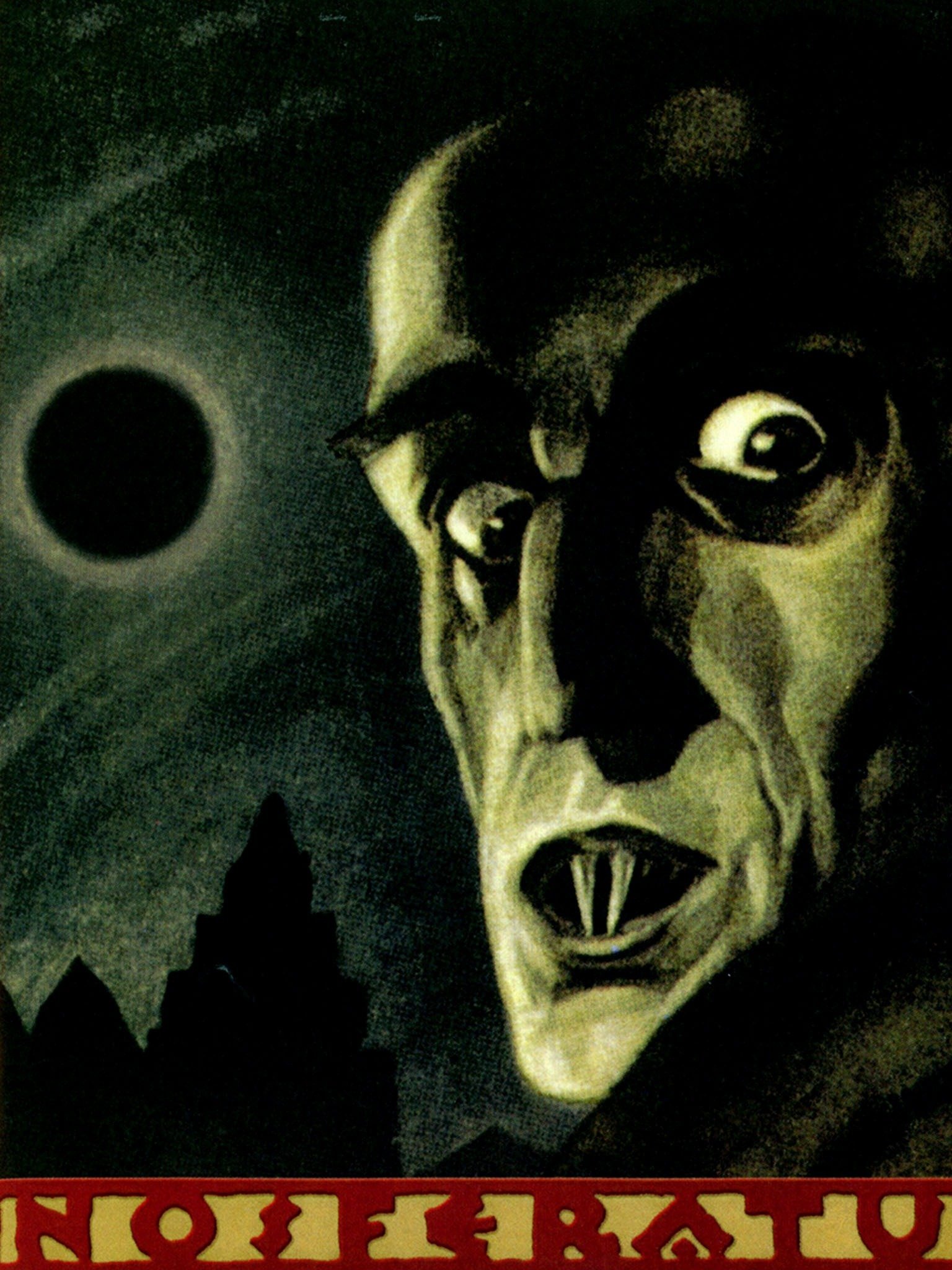

A retelling of the novel in all but name, F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) brought the Count (herein redubbed “Count Orlok”) to un-life. Vile and grotesque in his appearance (though still wholly different from Stoker’s description,) Orlok’s long, gangling limbs are spider-like and menacing, exaggerated by the deep, expressionist shadows that he casts upon the wall as he stalks his sleeping victims. Unlike his literary counterpart, however, Orlok has no bevy of seductive brides at his beck and call. Echoing the libertine Weimar Germany that begat the film, the vampire within this film seems to have no bias when it comes to the gender of his victims. Preying upon both Ellen and Hutter with equal interest. Hard-pressed to find anyone who may find the depiction of this vampire as “seductive,” the inherent eroticism of the vampire legend is nevertheless brought to bear as the Count’s tenebrous hands rove along Ellen’s unconscious body -- hovering over her breasts only to clench a fist across her heart. Ellen reacts in kind, arching her back and silently gasping in a manner that can be construed as both orgasmic and painful.

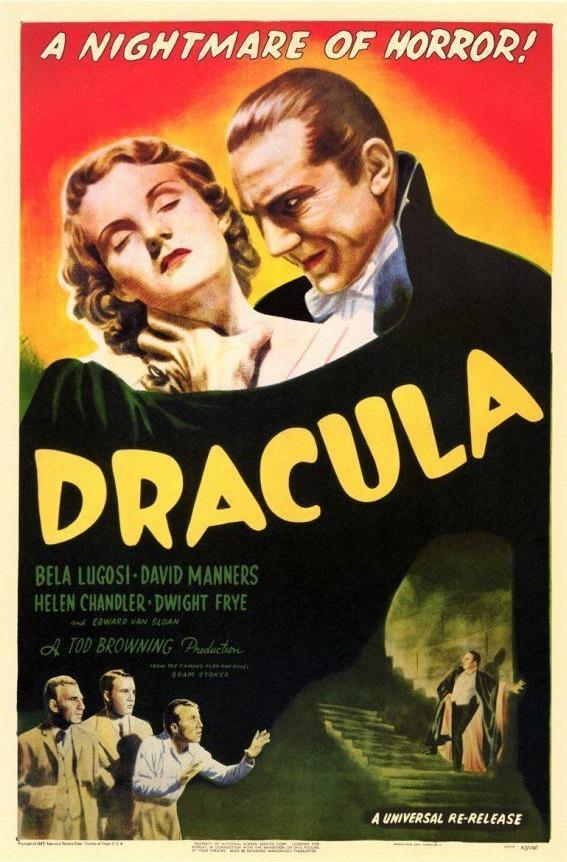

In Todd Browning’s legally licensed adaptation, Dracula (1931), we are introduced to a Count Dracula that follows legacy of Irving. Having portrayed the vampire in the 1927 Broadway adaptation, Universal Pictures cast Hungarian actor, Bela Lugosi. Exotic, intriguing and stately, Lugosi presented the Count as a refined gentleman, dressed in aristocratic blacks and whites, dressed as though out for a night at the Opera. The hypnotic effect of Lugosi’s eyes, however, are perhaps the most essential quality of his portrayal of the vampire -- with many shots lingering upon his key-lit gaze. “As Dracula emerges from the coffin, he stares straight at the camera, as though trying to mesmerize the audience,” bringing the threat of danger into the theater, itself, immersing the viewers in his ghastly presence. In this, Browning attempted to portray a vampire that could be alluring to women and dangerously threatening to men. (Kane 22)

Though iconic in appearance, noticeably Lugosi’s Dracula seems to be utterly devoid of fangs. Lugosi, himself, found it too difficult to enunciate his already broken English with them in his mouth. Additionally, in adherence to the Hayes Code, at no point in the film could the vampire actually bite one of his victims -- thus leaving many of the most tense scenes up to the audience’s imagination. “[T]hese factors conspire to eliminate a physical factor of the vampire the audience surely knew was there... The overall effect of the absence of fangs to make [Dracula] appear more human and less supernatural.” (Kane 24)

A notable inclusion in the Browning version is the presence of the three mysterious vampire brides, as mentioned in Stoker’s novel. Indeed, the concept of vampiric marriage is first introduced in Browning’s film. The Count’s ghostly harem, striding and silent, placate themselves before their ostensible husband -- bowing their heads in wordless deference. “[P]resenting Dracula as a polygamist in 1931 aligns the character with promiscuity and the diseases that were associated with such behaviour—themes accompanied by the bisexual overtones of the flm, which shows Dracula sinking his fangs into mortals of both genders.” (Lindop 168) Disease, in fact, both of the body and mind are a prevailing theme of Dracula (and, indeed, is implicit in most vampire fiction.) Professor Van Helsing and Doctor Seward, the heroes of the piece, work tirelessly to combat the strange affliction which seems to be besetting Lucy -- who has become corrupted by the vampires infectious bite. In a fevered craze, she ecstatically cries from her bed: “Lofty timbers, the walls around are bare, echoing to our laughter as though the dead were there... Quaff a cup to the dead already, hooray for the next to die!”

Yet, women are not the only ones who are subject to these contaminating effects. The Count’s first victim in the film, Renfield, is driven mad by his exposure to the Count. Though not a vampire himself, he becomes the eager thrall to the lordly Dracula. Wild-eyed and erratic, Renfield shocks his well-to-do peers with his inhuman fervor. He speaks of Dracula as a messiah-like figure -- omnipotent in his grandeur, with an almost religious reverence. “He came and stood below my window in the moonlight. And he promised me things, not in words, but by doing them!” Condemned to a lunatic asylum, Renfield’s love for Dracula echoes the contemporary viewpoint of homosexuality being a mental illness. Further, the Master/Slave relationship between Renfield and Dracula encapsulates a fetishistic Sado-Masochism -- best exemplified as Renfield begs for his master to punish him and torture him for his transgressions.

Though portrayed by various actors, the Universal Studios Dracula remained relatively static -- the aesthetics and attitude conforming to what was first embodied by Lugosi. In 1957, however, Hammer Studios’ The Horror of Dracula presented audiences with a fresh, frenetic take upon the vampire Count. Standing at 6’4, English actor Christopher Lee brought a looming, gargoyle-like intensity to the character. Taking advantage of the now lax censorship standards, Hammer also sought to return a sense of horror to the franchise. Further, as post-war paradigms shifted to more liberal leanings, the role of erotic sexuality within the vampire mythos began to take center-stage. In Horror, bright red blood and gore splatters the screen in vivid technicolor. Though the first in a growing trend, The Horror of Dracula began what author Tim Kane referred to as The Erotic Cycle of vampire films. “The interaction between vampire and his female victim appear somewhere between violent assault and sexual intercourse...The vampire often vacillates between extreme physical action and tender or erotic moments” (Kane 44). Hammer’s Dracula, blessed of Lee’s intimidating stature and booming baritone, was also the first to venture from the dusty, drafty halls of Victorian Carfax Abbey and enter the modern world. Thrust into a world of sexual liberation, films such as Dracula 1972 A.D. (1972) present the Count as an allegory for drug culture. A dark, mysterious, yet curiosity-inducing figure, whose indulgences lead to corruption, moral decay, death, or worse. To Lee’s Dracula, the swinging 60’s and 70’s of Beatles-era Britain presented a neverending smorgasbord of easily tempted souls.

Conversely, Paul Morrissey's Blood for Dracula (1972) presents a Count Dracula who is having a decidedly harder time acclimating to modern society. Morrissey introduces a new facet to the Dracula-mythos, the notion that he may only survive by imbibing the blood of virgins. As morals degrade throughout the ages, the abundance of virgins appear to become a more scarce commodity. Bafflingly, the film posits that the only way to save a would-be victim from Dracula’s depredations is to make them unappealing in their eyes -- which is to say to force sexual intercourse upon them. Blood for Dracula offers a story where not just the vampire -- but the vampire hunters as well, are monstrous in their deeds.

Returning to a more true-to-form adaptation of the Stoker novel, Universal once again donned the red-lined cape of the bloodsucker in Dracula (1979). Full of style, pomp and gothic romance, actor Frank Langella lessens the schlock horror monstrosity of Christopher Lee, and returns the subdued, gentlemanly nobility as once depicted by Lugosi. While evocative, however, Langella sought to hint at a certain depth within the mind of the immortal. "I decided he was a highly vulnerable and erotic man, not cool and detached and with no sense of humour or humanity. I didn’t want him to appear stilted, stentorian or authoritarian as he’s often presented. I wanted to show a man who, while evil, was lonely and could fall in love." (Film Review 25). Langella further went on to state: “Dracula seems to represent a kind of doorway to sexual abandonment not possible with a mere mortal. Besides, he's offering immortality. Actually, I can't think of a woman who wouldn't like to be taken if it's with love” (Sokol).

This premise of loneliness, and a love that was as immortal as the unbeating heart of the vampire, itself, reached a zenith in the high-budget, Francis Ford Coppola directed Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). As its namesake suggests, this version of the film drew more heavily upon Stoker’s original novel than any adaptation before it had even attempted. While at the same time, the plot introduces a number of new concepts -- deepening the relationship between Dracula and Mina and canonizing the connection between the fictional Dracula and the real-world source of his moniker, Vlad Tepes of Wallachia. Bram Stoker’s Dracula manifests a truly mercurial vampire, whose shapes and forms are as varied and endless as the myriad of actors who had previously worn the mantle. Depicted by character actor Gary Oldman, the Count of this film shifts between a ghastly and decrepit old man with Nosferatu-like fingers and hairy palms, a dapper and dashing “Prince Vlad,” who can integrate flawlessly into London society (while drawing the eyes of every female character, including background extras), and his true form -- the medieval knight, glorious in his stylized, demonic armor. The film’s promotional tagline: “Love Never Dies” seems appropriate, as the “sympathetic Dracula” is truly born within this film. Cursed from renouncing God after the death of his beloved wife, the historical Prince Dracula is condemned to life eternal, feeding upon the blood of the living within a dank and non-euclidean castle. His sole reason for existence to reunite himself with the reincarnation of Princess Elisabeta -- embodied within the form of Mina Harker.

Taboo and sexuality are at the forefront of the film, making the connection between sex, taboo and blood more explicit than ever. “As directed by Coppola, it is a lush epic in the David O. Selznick vein, but with contemporary sexual underpinnings and stylized blood-spilling” (Hart 9) A bewitched Jonathan Harker is beset upon by the nude forms of the vampire brides, Lucy is ravished by Dracula in bestial form -- who then writhes and moans erotically (much to the distress of the gentlemanly vampire hunters.) Upon her full transition she seems to become more insatiable and perverse than ever before. Indeed, even Dracula’s feedings (save those inflicted upon nameless side-characters) are presented even more lasciviously. Lucy smiles in delight when she senses her tormentor and lover is in close proximity. Mina herself begs for Dracula’s embrace, even when he himself is hesitant to bestow the curse upon her. “I want to be what you are, see what you see, love what you love,” she pleads with him -- only for Dracula to reply: “You'll be cursed as I am and walk through the shadow of death for all eternity. I love you too much to condemn you.”

The character of Dracula has shifted, fundamentally, from a bogeyman into a figure of gothic-romantic tragedy. One must wonder what Stoker would make of such a gentle vampire, or even Lugosi and Lee. There is an undeniable appeal, in one who possesses the immortality of youth combined with the wisdom of the ages, who can grant you the gift of everlasting life but at the cost of one’s soul. With such a tempting and attractive proposition, is the character of Dracula fundamentally not suited as a monster? “In America, literally hundreds of products using his name or his story have been marketed....Even a children’s cereal, Count Chocula, waits in the supermarket to entice the Sesame Street set, who have also learned to count in his name” (Wolf 166). Novelists such as Anne Rice, Charlaine Harris and Stephanie Meyer have all but concluded that the vampire serves chiefly as a romantic protagonist -- a fantasy for women readers and viewers. Though modern films such as Dracula 2000 and Dracula: Untold have attempted to return the character to his depraved and rapacious origins, the bats have already left the bell-tower.

Comments

Post a Comment